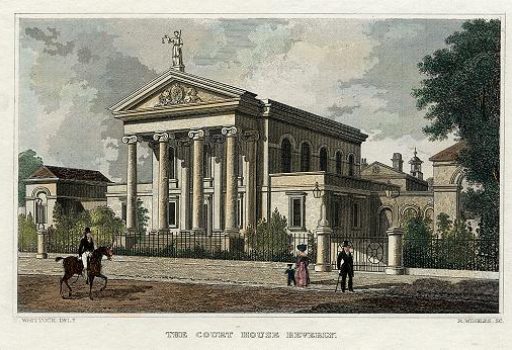

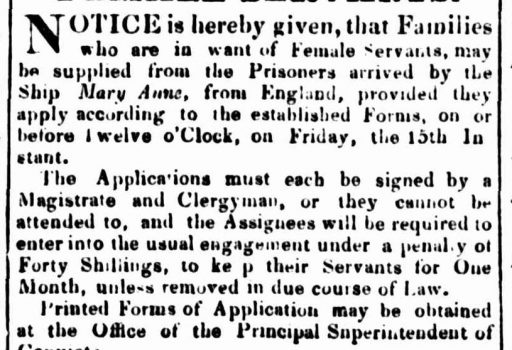

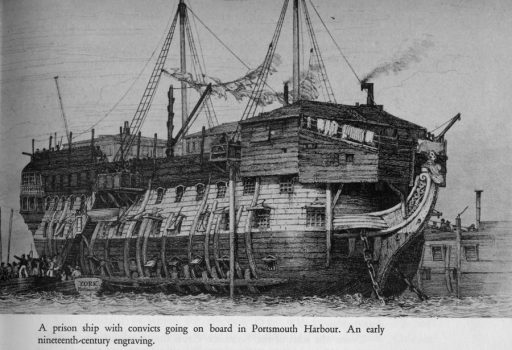

WILLIAM JUFFS and his father, agricultural workers from Houghton Conquest in Bedfordshire, were together convicted of housebreaking at Bedford Assizes in 1832 and sentenced to death. This was commuted to transportation for life for both of them (unlike in The Transports, where the father was hanged and the son transported). Their family was forced to enter the local workhouse. The convicts were transferred to the Justitia prison hulk in the Thames, where Juffs senior died, presumably from the hard labour. William arrived in New South Wales on the Parmelia in late 1832, finally received a pardon in 1846 and died at Gundaroo in 1852.

GEORGE RAWLINSON, a 23-year-old shoemaker and son of the landlord of the Red Lion in Bierton near Aylesbury, crossed the county border to break into a house near Tring. He stole five watches, was caught and went up before the Lent Assizes in Hertford in March 1862. There he confessed of his own accord to also stealing a pair of boot trees from Francis Kingdrell. He was sentenced to six years servitude. From Hertford Gaol he moved to Millbank prison, then Pentonville and finally Portland, where he faced hard labour in the infamous local stone quarries. No wonder he volunteered for transportation which, at that time, must have been an attractive option for someone young and single. He arrived at Freemantle on the Lord Dalhousie in December 1863. Within three months he married Margaret Coghlan who’d arrived from Ireland on a ‘bride ship’ and he started working as a servant in Perth. By 1868 he was free to move, and the family settled in North Adelaide, where he and Margaret were to have five children.

HENRY CATLIN had a sad childhood in Bedford. Born in 1827, his boot-maker father was a violent drunk. Henry’s mother died when he was eight. The father could not support the seven children. At nine-years-old, Henry was caught with a stolen pair of shoes and sentenced in Bedford to four months hard labour. Later aged 14 he was caught stealing three and sixpence. This time he was sentenced to 14 years in Van Diemen’s Land. In the same sessions his father was sentenced to seven years for stealing two shillings; he stayed on the prison hulks, while young Henry sailed on the Asiatic in 1843. Though the food was meagre during the 110 day crossing, it was more than he’d been able to rely on at home. By 1852 he’d received his pardon and soon married Harriet Coffee in Hobart. They moved to Bendigo, tried and failed at gold-mining, so Henry started making shoes, like his father. They had seven children that survived. Henry lived to the age of 91. He might well not have lasted that long back in Britain.

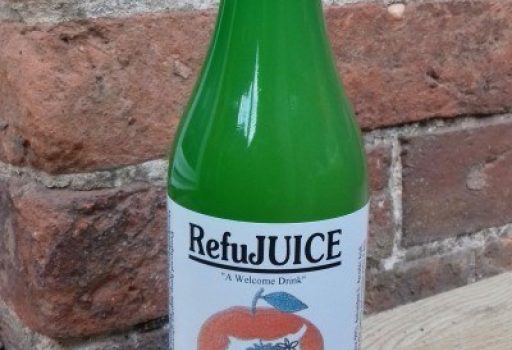

‘We are all foreigners in Milton Keynes’ ‘Due to the sense of superiority of native-born people, racism is a common phenomenon in Britain. But I don’t think it is as common here as in other cities, because there were not many native-born people in Milton Keynes. Most people seemed to be moving in from somewhere else. It can be said that we are all foreigners in Milton Keynes.’ Samuel Wong, quoted in Living Archive Milton Keynes.

RUTH DESALE faced the threats of arbitrary arrest, torture and forced labour in her home country of Eritrea. These dangers were particularly acute because her family were Pentecostal Christians. Joining a group to escape the country, she survived a hellish journey across desert in Sudan, then embarked on a dangerous crossing from Libya to Italy. Her smuggler’s boat started to sink, like so many. For a while, there seemed no hope and those on board prepared to die. Then, by miracle, an Italian Government ship arrived to rescue them. Ruth’s journey brought her finally to Milton Keynes where, still a teenager, she started to make a new life. Ruth’s story comes from a report on ITV News Anglia.